Of his 77 years on Earth, John C. Frémont (1813-1890) spent just one night–maybe 12 hours tops–in Las Vegas. That was exactly 180 years ago this week, on May 3, 1844, when the Mojave Desert area’s only significant population were Indians, a racial group that Frémont, a military officer and future presidential candidate and celebrity, despised, disparaged and sometimes massacred (along with the occasional Latino). Illegally mapping Mexican territory for a future gringo invasion that he eagerly joined and profited from on the basis of inside information, Frémont with his well-armed troops took off early the next morning for nearby Utah and never returned. The entire account in his famous journals of his one-night stand in Las Vegas fits into a single paragraph in which he mainly obsessed about the warm water.

Yet Frémont’s identification with Las Vegas remains eternal. Long before the Las Vegas Strip there was Fremont Street. The east-west artery cutting through downtown Las Vegas was the heart of gambling after the State of Nevada legalized casinos in 1931. The state’s very first gaming license went to the Northern Club at 15 E. Fremont St. Even as the casino action eventually migrated southward to grander facilities along S. Las Vegas Blvd.–the Strip–Fremont Street held its own. It was on Fremont Street that Buddy Binion’s Horseshoe Casino in 1970 started the World Series of Poker, now the world’s largest such tournament.

Today, there’s the Fremont Street Experience, a five-block-long pedestrian mall festooned with neon, much of it under a 90-foot-high canopy. After the Strip, Fremont Street is undoubtedly Las Vegas’s best-known street.

The adulation of Frémont in Las Vegas continues to utterly mystify me, but praise is not limited to hereabouts. Mainly across the West, cities, counties, neighborhoods, rivers, mountains, streets, schools, libraries and hospitals are named for a man that many Americans today vaguely remember–if they do at all–only from high school American history classes. In my view Frémont was the luckiest U.S. war criminal of the 19th Century.

Much of this essay is drawn from posts I have written over the past dozen years, stretching back long before I became New to Las Vegas.

A Georgia native born out of wedlock, Frémont was expelled from military college for bad attendance. Nevertheless, he eventually joined the Army. Largely inept as a soldier, he found he had a terrific sense of P.R. and an extraordinary amount of good fortune. One big break: He married Jessie Benton, the talented daughter of a powerful U.S. Senator from Missouri in a tremendous position to advance his career. For much of his exploratory career Fremont was a second lieutenant.

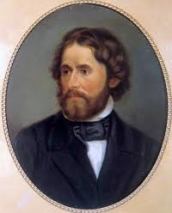

The good-looking Frémont, who held a high opinion of himself, cultivated the press and got insanely favorable coverage. During his explorations he was a probably was the country’s best known military officer, which was saying something. (How many second lieutenants can you name?) The scribes called Frémont “The Pathfinder” or even “The Great Pathfinder” for his mapping (and spying) expeditions across the West, then part of Mexico. Most of the time, though, it was his equally famous sidekick, Kit Carson, doing the pathfinding. However, Frémont had a way with words; it was he who dubbed the entrance to San Francisco Bay the Golden Gate.

Fremont’s encounter with Las Vegas occurred on the second of his five expeditions through the West, in 1843-44, during which he and a group of well-armed “topographical engineers” with horses and mules explored the future Wyoming, Idaho and Oregon and Utah before heading south into the future Nevada. He almost lost his life, and those of his troops, trying despite the advice of locals to cross the Sierra Nevada in the dead of winter 1844 just south of Lake Tahoe into California. Somehow, he made it, but only after abandoning armaments and eating some of their horses to stay alive.

The expedition headed south through California’s San Joaquin Valley, then in early spring 1844 made a left to the east north of Los Angeles, crossed the Sierra Nevada over Tehachapi Pass and eventually picked up the Old Spanish Trail. That was a 2,700-mile long circuitous trade route running between Santa Fe, N.M. and the Los Angeles area that had been documented–in Spanish–by others 15 years earlier.

Heading northeast, Frémont and his troops occasionally clashed with local Indians, whose lands, of course, they were invading (Mexico, the legal authority since ousting Spain in 1821, had little clout in the region). Frémont in his writings praised Carson, in particular, for what what one historian has called his disproportionate “butchery” in killing Indians to avenge deaths and get back stolen horses. Frémont blandly wrote in his journal that Carson “had been able to give so useful a lesson to these American Arabs.”

Frémont crossed into Nevada near Pahrump on April 30, 1844, and eventually followed eastward what roughly is now the route of State Highway 160 for 60 miles over three days. It was then he encountered for the only time in his life the pleasures of the future Sin City.

Here, in its entirety, is the passage about Las Vegas in Frémont’s journal:

May 3–After a day’s journey of 18 miles, in a northeasterly direction, we encamped in the midst of another large basin, at a camping ground called las Vegas–a term which the Spaniards use to signify fertile or marshy plains, in contradistinction of llanos, which they apply to dry and sterile plains. Two narrow streams of clear water, four or five deep, gush suddenly, with a quick current, from two singularly large springs; these, and other waters of the basis, pass out in a gap to the eastward. The taste of the water is good, but rather too warm to be agreeable; the temperature being 71 degrees in one and 73 degrees in the other. They, however, afford a delightful bathing place.

May 4–We started this morning earlier than usual, traveling in a northeasterly direction across the plain …

That was the totality of Frémont’s stay in Las Vegas, except for a parting shot that the local Indians, the Southern Paiutes, were “lizard eaters.” Frémont headed toward Utah again, roughly paralleling the future Interstate 15.

Frémont likely had camped in the vicinity of the Springs Preserve, now a Las Vegas park and minor tourist attraction. It’s also the site of the Nevada State Museum, Las Vegas, which, in 2018, mounted a glowing exhibit of Frémont in Nevada that was pretty much a total whitewash by leaving out all the considerable bad stuff. A museum official I debated at the time on the local NPR station acknowledged I was correct. (The springs, by the way, had long dried up.)

Ten thousand copies of Frémont’s journal, including a map that clearly marked Las Vegas, were published in 1845 by the U.S. Senate with the help of his father-in-law and the editing of Fremont’s wife under the title Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains 1842 to Oregon and Northern California in 1843-44. For a government document, it was a publishing sensation, a highly readable tale of derring-do and adventure–and murder–in still unknown lands. The report made Frémont’s very famous, especially after many newspapers reprinted large portions.

The report popularized for a English-speaking audience the Old Spanish Trail. It is credited with guiding thousands of gringo immigrants to the West. They included Brigham Young and his Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormons) to Salt Lake City in 1847 (lured there partly after Frémont wrote incorrectly that part of the Great Salt Lake was fresh water without salt) and hoards of fortune-seekers after the 1848 discovery of gold in California.

There is no record that Frémont, who was promoted to captain, ever again set foot in Las Vegas, either as a military man or as a later politician and celebrity. He did come through Nevada again on two later military expeditions. It appears from maps of his route that on his fourth expedition in 1853-1854, traveling westward from Pioche to Beatty, both places north of Las Vegas, he passed through what also would become another very famous locale in the 20th century–Area 51, the super-secret military reservation 150 miles north of Las Vegas.

Frémont’s first three expeditions through the West eventually became part of U.S. President James K. Polk’s implementation of the policy of “manifest destiny.” That was the notion of a God-given right that the United States, then confined to the eastern half of North America between Canada and Mexico, should grab the other half, especially California. Latinos and Indians be damned, if Yankee Gringos hankered after their land, which, of course, they did.

In Match 1846, ordered by Mexican authorities to leave California, Frémont and his men headed north toward Oregon, not part of Mexico. In the process they attacked without provocation a large Indian encampment near the future Redding, Calif. Their long guns allowed them to fight with impunity from outside the range of answering Indian arrows. In what became known as the Sacramento River Massacre, Frémont’s troops easily killed hundreds of braves, women and children without experiencing any casualties of their own. Trapped by the Sacramento River, many others died from drowning.

In Oregon, Frémont experienced some more luck. Polk, unquestionably America’s most effective one-term president, made his move, ginning up the Mexican War starting in April 1846. Polk sent a courier West with orders for Frémont to return to California.

But Klamath Indians upset about the U.S. incursion into their ancestral trial area and understandably fearing the worst attacked Frémont’s unit and killed three men. He ordered retaliation on a disproportionate scale. His troops sent several days moving around the 87-mile perimeter of Klamath Lake killing every Indian they could find–as many as 14 at one time–and making little effort to determine the guilty parties. Since Frémont’s troops again had the guns and the Indians again had only bows and arrows, it really wasn’t much of a fight. His men found it particularly sporting to pick off Indians at long range.

Now a genuine war criminal, Frémont expressed great satisfaction with his actions. “It will be a story for them to hand down when there are any Klamaths on their lake,” he said.

There’s more. Frémont and his fellow killers returned to Northern California. His troops stole horses, raped Indian women and shot their husbands. “We killed plenty of game and an occasional Indian,” wrote one of Frémont’s soldiers. “We made it a rule to spare none of the bucks.”

He wasn’t referring to elk or deer.

The Mexican War was still underway in June 1846 when Frémont’s army reached San Rafael, just north of San Francisco. His troops spotted three innocent, unarmed Mexican settlers–an elderly man and two nephews–crossing a waterway toward them. Using a telescope, Frémont himself watched the small boat as it neared the shoreline.

“Captain,” Kit Carson said, “Shall I take these men prisoners?”

Frémont airily waived his hand. “I have no room for prisoners,” he replied, according to a witness account the Great Pathfinder never disputed. His answer amounted to a death warrant. Using their rifles at point-blank range, Carson and two soldiers eagerly gunned down the helpless Californios.

They then reported back to Frémont what they had done. “It is well,” he said approvingly. His soldiers then stripped the dead bodies of all clothing. Frémont rebuffed one dead man’s son who asked for return of his father’s poncho.

For Frémont, the rest of the Mexican War solidified his reputation as a man of action, if nothing else. He quickly captured largely abandoned Monterey, the Mexican military capital of California south of San Francisco, then sailed down the coast toward Los Angeles. Team Frémont triumphantly marched into the City of Angels but was forced to retreat by outraged civilians who were better shots. But in early 1847 he returned, signing (without any authority whatsoever) the cease-fire that essentially ended the Mexican War and firmly brought California, Nevada and a chunk of the West into the U.S.

If they’re on the wining side, war criminals are never made to truly account for their atrocities. That certainly was true of Frémont, although he was court-marshaled and given a slap on the wrist, not for the massacres, but for insubordination, essentially showing up his superiors. Meanwhile, he bought a 44,000-acre ranch near California’s Yosemite Valley (using proprietary information he gained while surveying the land for the military) from someone who did not have clear title. When gold was discovered in the vicinity–that old Frémont charm again–he worked to alter the boundaries of the defective deed to cover some of the gold lands and evict miners already at work there.

The maneuvering made him for a time very, very wealthy. Yet he balked at paying his local property taxes. That prompted the Sacramento Bee to editorialize, “It is hard to wring taxes out of rich men. Small property holders pay taxes with grace, but large ones never, if they can avoid it.”

In 1850 Frémont became one of California’s first two U.S. senators, chosen, as was the method then, by the state legislature, dominated by Yankee interests, for the short inaugural term of two years. But he spent so much of his time looking after his land holdings that disgusted lawmakers denied him a full six-year term.

That hardly stopped him. In 1856 the fledgling Republican Party chose this war criminal as its first presidential candidate. His status as an anti-slavery politician reared in the South held some appeal in the North. Still, he lost nationally to the Democrat James Buchanan in a three-way race. Frémont really lost California, not even mustering 20% of the popular vote. In the area around his ranch, he got only 6%; in some precincts, 0%. (In case you wonder, Nevada didn’t become a state until a few days before the presidential election of 1864, in a sketchy deal rigged by Abraham Lincoln, so no one there could vote for or against Frémont in 1856.)

Five years later, he rejoined the military on the Union side for the Civil War, promoted to major general, but fellow Republican Lincoln fired him for grandstanding on the issue of slavery (Frémont wanted to push for abolition far faster than his Commander in Chief). After the war Frémont peddled worthless bonds in Europe for a dubious U.S. railroad, blew through his gold fortune and went bankrupt. He also served three years as the presidentially appointed governor of the not-yet-a-state Arizona territory. Frémont died in 1890 broke but famous and celebrated in many, many circles.

Frémont did not found Las Vegas. The area’s non-Indian population in 1900, 10 years after he died and 56 years after his one-night stand, was only 18. The count was so small all the residents fitted on one page of the U.S. Census enumeration. Las Vegas as a populated place came into being in 1905 when William A. Clark, the corrupt Montana mining tycoon building a rail line from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City, auctioned off 1,100 lots around the future Las Vegas train station. He’s the namesake of Clark County, where Las Vegas lies. With a population today of 653,000 Las Vegas is the biggest U.S. city started in the 20th Century.

I invite readers to comment below on my perceptions. Whatever others might say about Frémont’s career, there’s one thing I know for sure about his sole night in Las Vegas 18 decades ago. Like hundreds of million of tourists who would follow him, he got a good bath.

Excellent.

Brigham Young was on his way to San Francisco to meet up with other LDS pioneers who took a boat around South America.

Thanks.

A truly wonderful read – many thanks